The Problem of True Identity

INTRODUCTION

Imagine, for a moment, that you are the new night guard in some very secretive government facility. One night you are roaming the empty halls when you suddenly come across a laboratory containing a strange, glowing tank – almost sentient – glimmering with incandescent green liquid. You peer through the glass and see a solitary brain floating there, wired to various electrical devices resembling cathode tubes attached to rows of miniature transformers. There are waves of silent electricity exuding, like muscular pulses, from the liquid. The brain is obviously alive, probably thinking. Your curiosity gets the better of you and after a quick glance out into the empty hallway you decide to investigate further. A nearby desk has a single manila file folder laying on its surface and you pick it up. On the tab is written a name – your name – followed by a string of numbers. Your doubt increases (you look around for hidden cameras, thinking it to be some sort of joke at your expense) but sheer curiosity wills you toward the vat. As you hold the manila folder shakily in your hand, you slowly lift it and compare the string of numbers following your name to a string of numbers, resembling a serial code, on the side of the tank. They match.

What now? What is the proper course of action following this realization? Here you are, standing in the presence of what appears to be your own brain in a vat. What next? Do you dare to press some buttons found on the side of the tank, in order to test the validity of this finding, or do you ignore the tank, quit your job and immediately seek new employment (and the aid of a psychiatrist)?

In order to dissect this problem further, a few possibilities must be considered:

PART I

IS THE BRAIN YOU?

If you choose to tamper with the brain, will your reality change? Will you suddenly awaken to the senseless prison that is this floating organ (or to some other manner of consciousness)? Will you simply cease to exist altogether, or is the encounter with this mysterious, floating organ itself only part of a greater illusion (which it must be in this case, because no one can, in the scope of known physicality, look at one’s own brain from without)? This question (Is the brain you?) suggests the possibility that the brain present before you is the product of a synthetic, hallucinatory reality.

In order to prove or disprove this hypothesis, one is left with two options: 1) Tamper with the brain, even at the risk of one’s own destruction; 2) Leave it alone. There is nothing in your immediate observation to convince you that tampering with the brain will have an affect on your reality. What if, after destroying the brain, nothing happens? This would provide no solution at all but only leave you with the possibility that the brain was either an entirely separate individual; a possible copy of your own brain, separate from your own mentality; or simply a powerless hallucination.

IS THE BRAIN ANOTHER YOU?

You then think back to your job interview. You were asked, by an exceptionally stoic man in a white lab coat, to provide a blood sample before beginning work. The secretive nature of the government facility to which you’ve been hired eludes you. You wonder if it is at all possible that you were subjected, like a guinea pig, to some bizarre form of scientific testing involving human cloning. You wonder about the nature of the brain enclosed behind that glass, submerged in green liquid conduit. Does it think? Is it dreaming – lost in a hallucinatory world that it believes to be true, sensing and interpreting electrical impulses administered to provide its consciousness – or does it know it’s trapped? Does it share your memories? Does it think it’s you?

In this case, the same two options apply: do you test this validity by tampering with the brain, or do you simply walk away and try to ignore what you’ve seen? At what point can you accept your perceptions without simply submitting to the possibility of a disingenuous reality?

PART II

PROJECTED IDENTITY AND SELF-AWARENESS

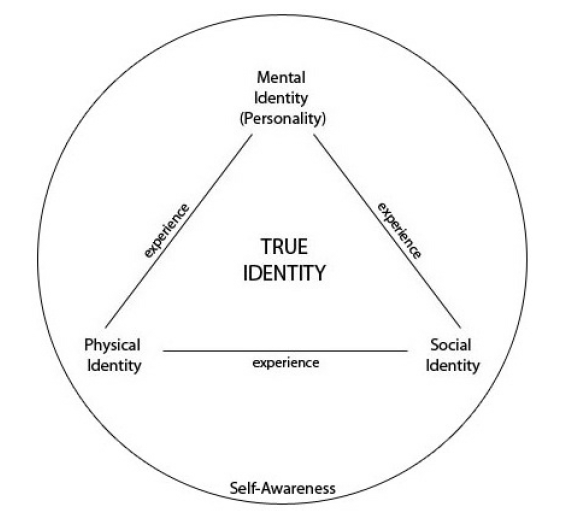

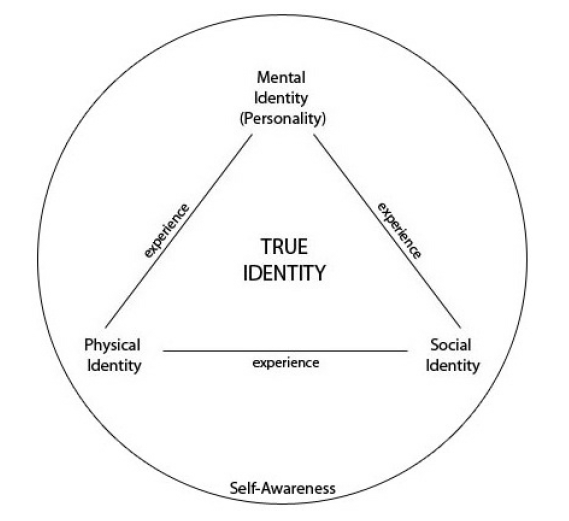

One’s awareness of one’s own existence is a common and unspecific attribute, an attribute that does not alone make an individual uniquely identifiable. The anthropologist Adolf Bastian pioneered the concept of the “psychic unity of mankind” – the idea that all humans share a basic mental framework. It is my intuition that in order for one to build an identity of any kind, there must first be some original, common basis upon which human identity can be developed. I believe this basis to be the act of self-awareness (or Cartesian doubt).

In the liminal state between mere existence and self-awareness, all mental identity (self-perception) and, subsequently, experience is absent. In the state where one exists either previous to or absent of self-awareness and experience (perhaps a fetal state, or in death), identity is merely a projection from social relations based on physicality. In this state, though the physicality identified with a person by his or her social relations may exist, there is no “self” involved. A mother may imagine the identity of her unborn child but any truth in this identity will be superficial, based on physicality and her relationship to the fetus alone, and involving no personality. Similarly, in death, though the “self” of the deceased has waned, an identity is projected by those relatives who knew him based upon their relationship to him and his remaining physicality. Both a fetus and a cadaver exist in a state of projected identity, based on physical and social identity but absent of self-awareness, and, hence, true identity. Without this basis of self-awareness, true identity cannot exist.

TRUE IDENTITY

At what point does a clone cease to be its original? To examine the identity of a clone, we must first attempt to understand the identity of the original. Even throughout the life of a single man, his personality, his outlook on life, what one might call his “identity” may change several times. By the time a man is middle-aged, he may look back fondly on his youth and think, “I am not the man I used to be.” What, exactly, does this statement imply? It is apparent that the experiences the man has collected throughout his life have each altered him in one way or another. Be it by his changing social relationships, his acquiring of knowledge, physical injury, etc., he has encountered outside forces that have influenced his being. But what does this mean for the nature of identity? Does true identity continue or change based on experience? I use the term, “true identity,” meaning that manner of existence and being of which the man uniquely identifies himself (physically and mentally) in congruence with that projected identity of his social relations. To better understand this state of “true identity,” I will divide it into three distinct, but reliant, subsections: Mental Identity (or personality and self-perception), Physical Identity, and Social Identity.

Those encountered, outside forces that have influenced the man’s identity will be referred to as “experiences.” As the man has aged and gained experiences, these life experiences have certainly altered the nature of these three subsections of the man’s identity, although his “true” identity has ultimately remained the same. Although the man has undergone changes in his life, perhaps to the extent that his present condition is nearly unrecognizable to his former, he is still identified as the same individual. This continuation of true identity is based on the perceived continuations of his physical, mental, and social identities. These perceived continuations, in turn, are based on “experiences” – or some encountered forces that have each affected at least two of his subsections of true identity. The man’s mind has shared experiences with his physicality – or with his sociality, or any pairing of the three – continuously from his youth into his middle age, thus continuing his true identity. True identity cannot be maintained without the continuity of at least two of these subsections at all times, held together by experiences, and built upon the basis of self-awareness.

If the man were to awaken one morning to find that he has become a woman, is sleeping in a strange bed, in a strange house, in a strange city, and has strange friends who identify him (or her) by a strange name, then regardless of the persistence of the memories that his mind would initially retain, his mental identity would naturally begin to change in order to conform to his new physical and social being. Thus, two of the subsections of identity having been altered, this would lead to an entirely new variant of true identity. With the changing of this man’s physical and social identities, all that would remain unchanged is his own mental self-perception, which would become unsubstantial and malleable without physical and social support. If I were to perceive myself to be a salamander, this would not make it so without either physical or social support. Put simply, true identity follows the identity of the majority of its subsections. This remains true for any pairing of the three subsections. If I were to perceive myself to be a salamander and had the social support of my peers, who also perceived this to be true, then it would give me cause to doubt the nature of my physicality.

In the case of a cloned identity, as soon as the clone becomes self-aware, it is then in possession of the basis necessary for the creation of an individual identity. As soon as the clone perceives a unique experience, it makes the pairing necessary to solidify any two of the subsections of identity. Though the clone may share common memories with his original, he is now a separate, unique individual, in possession of a true identity, no matter how similar to his original.

A NOTE ON “PERSONAL IDENTITY”

Derek Parfit questions the continuity of identity in the face of brain transplantation and/or lateralization. In an operation where a brain is separated into two (left and right) hemispheres, and one hemisphere is transplanted into a different body, where does the identity lie (with the original body, the new body, or both simultaneously)? My answer to this would be that two distinct identities are created. Even in the case of brain lateralization, where the bridge between hemispheres is severed while within a single body, the result is “two separate spheres of consciousness,” (Parfit 1971:6) each of which exists and functions independently of the other. In this case (analogous to cloning), according to the guidelines I have set for “true identity,” this occurrence creates two individual identities, regardless of their capability to re-synthesize into one. The separate spheres of consciousness have separate self-awarenesses and, as such, while separated, cannot be one in the same.

TRUE EXPERIENCE AND SYNTHETIC IDENTITY

The continuity of each of these subsections of identity is governed by experience, or that manner of external force that has affected at least two of the subsections. Essentially, in order for an experience to be true (to have an affect on true identity), it must affect at least two of the subcategories of identity. For instance, a dream that is experienced only by the mind is not a true experience. It becomes true only after it has an effect on either a person’s physical or social identities. If a young child dreams that he has wet the bed, it is not a true experience unless either he has also physically done so, or the mental effect of this dreamed action has become so strong that it effects his social identity in the same way as if he had physically done so (say, for instance, he develops a complex about it that alienates him from his peers as a result). All true experience, then, either past or future, thus relies on the existence of at least two forms of identity – in the same way that a bridge relies on two forms of land. Therefore, if the case should arise that two subsections of identity become changed, then whatever experiences are shared between a changed and unchanged subsection become irrelevant – broken links associated with merely an aspect of identity rather than the true totality. In this case, the experience must be deduced; a synthetic experience (such as a dream) rather than a true, effective one. In the case that two of the subsections of identity should fail completely, true experience becomes completely negated and true identity must be rebuilt (if possible, from the basis of self-awareness) on new experiences and whatever subsection remains. If a wounded soldier wakes up in a military hospital, suffering from amnesia and a mutilated body, he must recreate his identity based solely on social relationships and whatever new experiences may be earned thereafter.

So in the hypothetical that you may stumble upon what is apparently a clone of your brain in a vat, though the clone-brain may perceive (hallucinatory) experiences and the continuance of all three branches of identity from the point of clonal separation, this continued identity is merely synthetic and superficial in that it really exists only in the mind of the clone-brain and, hence, in only one subsection of identity. (In the case of a full-bodied, physically and socially identical clone, this continued identity would be true but, again, the clone’s possession of a separate self-awareness would create a new, unique (though similar) identity.)

PART III

THE BRAIN IS NOT YOU.

After much contemplation on the nature of the floating brain that you have found in the vat, you have decided that there are only three conclusions to be drawn about its existence. It is either: 1) a separate, though possibly similar, cloned identity; 2) your own mental hallucination; 3) an unknown variable – a completely unrelated brain either mislabeled or coincidentally labeled with your name (this third option, as equally more likely as it is vapid, offers even less provability than the first two and will be ignored for the sake of argument).

As previously stated, there are only two methods available for testing these hypotheses: to either tamper with the brain at the risk of self-destruction or leave it alone and try to ignore your findings. In the case of tampering, there may arise certain moral issues. If it becomes the case that the brain is possibly a separate individual, there may arise a moral issue concerning the personal rights of an individual to not be pestered, mutilated, or murdered by another – even if their reality is synthetic and superficial (though, in this case, I think anyone might consider your actions to be personal and justified). In the case that the brain is your hallucination, the only moral issue is the risk of self-mutilation or suicide. However, this begs the question of the nature of self-perception in the presence of the hallucinatory.

If you were to tamper with the brain and no reaction ensued, there would be still no conclusion because it could either be a separate individual or a powerless hallucination (a hallucination whose presence has no repercussions for the structure of the surrounding reality). If you were to tamper with the brain and your surrounding reality were to become somehow altered, then the brain would prove to be a powerful hallucination (that which has the ability to reveal something about the nature of your perception of reality).

It might be assumed that if the brain in the vat is taken to be a hallucination, there is nothing to restrict that hallucination to merely the presence of a single object. In other words, the brain might only be part of a much greater (perhaps all-encompassing) illusion. If this were the case, as would be evidenced if tampering with the brain caused your reality to change, then your self-preservation would be the preservation of merely a synthetic identity. If all reality is hallucinatory, meaning you have no true experiences by which to form a true identity, then any identity becomes synthetic or projected and all that truly remains is that original basis of identity: self-awareness (or Cartesian doubt).

YOU ARE THE BRAIN.

When one considers the nature of this hypothetical (the problem of one stumbling upon ones own brain in a vat), then it becomes apparent that there is no demonstrable difference between this hypothetical and any normal state of existence. All three of the subcategories of true identity are founded upon a synthetic understanding, much like that of the possible hallucinatory and synthetic reality created and perceived inside of the brain in the vat. In other words, there is no demonstrable difference between the brain in the vat and the brain in your head. Just as the perceived reality of the brain in the vat can be completely hallucinatory, so might be your own reality, begging the question of whether or not your true identity (both physical and social subsections) actually resides on some different plane of consciousness apart from your mental perception.

Though the brain in the vat offers a method by which prove its hallucinatory nature, there remains no way to disprove it (if tampering with the brain offers no change to your perception of reality, it might simply be a powerless hallucination). The brain in your head works in much the same way. I would almost guarantee that if you were to gain access to the inside of your skull and tamper with your own brain, in your head, it would alter your perceived reality in a very similar manner as would tampering with the powerful hallucination of the brain in the vat (of course, if you were to tamper with the brain in your head and nothing were to change, it might be equally telling).

PART IV

UNDYING OPTIMISM

This is a basic problem of philosophy: the attempt to discover the connection between mental perception and physicality. Though I may propose the criteria necessary to form true identity, I cannot profess any method by which to demonstrate the validity of those criteria without running the risk of self-mutilation or self-destruction. As Hume outlines the problem of induction, that all objects of human inquiry and reason are divided into two kinds: wit or matters of fact, I must conclude that the precise relationship between physicality and mentality cannot be logically deduced through the use of human wit. It must only be discovered and experienced as a matter of fact. In short, the only way to realize an understanding of this link is to experience either one’s own birth or death, options that leave little hope for the optimist. This becomes a circular argument, as any experience of the creation or destruction of the physical and social ties to one’s mentality would be a synthetic experience (one experienced only in the mind) and, hence, not a true one.

I would risk the negation of my own argument, then, to state that no form of true identity is possible to achieve without first submitting to the possibility of a disingenuous reality (which would also make any identity synthetic). If one does not wish to submit to this possibility, then one must accept that true identity is impossible; in which case all that remains is that original self-awareness (or Cartesian doubt), the only aspect of perception that can be entirely trusted.