Wabi-Sabi and the Temple of the Peaceful Dragon

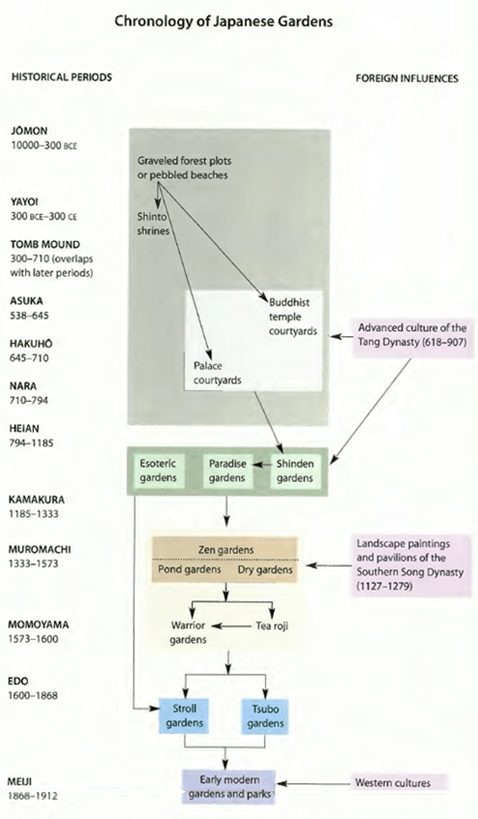

Gardening has been a cornerstone of Japanese culture for thousands of years, evolving from simple gravestones into meticulously crafted artscapes. The first pebbled clearings appeared on the island nation some two thousand years ago, created as ceremonial spaces honoring the spirits (known as kami) that were believed to have emerged from the sea. Over time, these clearings developed into the graveled courtyards of Shinto shrines and, eventually, into the Buddhist gardens that are the archetype of Zen landscapes.

The art of gardening was refined over many centuries to serve the needs of royalty, aristocrats, temples, and shrines. It is entwined with Japanese philosophy and steeped in a tremendous wealth of history. Devotion to this craft resonates to the core of Japanese cultural identity, from the animism of Shinto to the simplicity of Zen to the natural beauty of wabi-sabi. It is an intricate artform whose elegant simplicity has found new meaning in our increasingly modern societies, reminding us of the essential connection between nature and the human soul.

To give a better sense of how Japanese gardens developed and what this artform means to the Japanese identity, let’s take a brief look at how that identity is tied to the landscape of Japan itself. Sometime before the end of the Pleistocene era, the islands of Japan became inhabited by Paleolithic hunters and gatherers from the East Asian mainland. Some of these people reached Japan via the northern island of Sakhalin (modern-day Russia), while others arrived by boat from China and Korea.

During the Jomon period (10,000-300 BCE), pottery was developed, and inhabitants began to cultivate wet rice fields. Then, in the Yayoi period (300 BCE-CE 300), new cultural influences arrived from the mainland, bringing with them a more settled way of life supported by this irrigation agriculture. It was during this period that the Japanese indigenous mythology began to develop into a more unified religion known as Shinto, the ritual worship of the kami spirits that are believed to dwell in natural objects. Toward the end of the Yayoi period, burial mounds appeared, built for important community leaders. It was during this Tomb Mound period (ca. CE 300) that Japan began to resolve centuries of conflict between rival clans and unify under the leadership of the Yamato clan, from which the present imperial house is descended.

Buddhism was introduced to Japan some time in the sixth century by Chinese monks traveling through Korea. With Buddhism came the adoption of the Chinese writing system and a governmental legislative structure modeled after the Chinese Tang Dynasty. But Japan would break contact with the mainland and adapt its newly imported knowledge into a uniquely Japanese culture. This formative era would later become known as the Nara Period (710-794), so named because of the new capital established in the present-day prefecture of Nara where major Buddhist denominations began to establish their temples. This was the apex of Buddhist culture in Japan, which arose alongside the formation of the Japanese Shogunate, a feudal form of government run by territorial warlords.

During the Muromachi Period (1333-1573), under the feudal rule of the Shogunate in Kyoto, Japan saw a great flowering of Zen-inspired arts like calligraphy, flower arranging, martial arts, and landscape gardening. After the unfortunate destruction of much of Kyoto during the Onin War (1467-1477), the capital was moved to Edo (modern Tokyo), leading to nearly 300 years of relative peace, stability, and isolation. It was not until the mid-1800s that the rulers of Edo began to feel dissatisfied with the pace Japan was keeping with the West, and so with the Meiji Restoration (1868) they abolished the shogunate and restored the emperor to power. From this point, Japan embarked on a program of rapid modernization, industrialization, and urbanization.

The Japanese garden as it developed throughout this isolationist period became–perhaps unsurprisingly–distinct from the styles of Western gardens. As Michiko Young states in her book The Art of the Japanese Garden,

In Western societies whose cultures are fundamentally European in origin, the word “garden” means a place where things are grown, as in “vegetable garden,” “flower garden” or a formal garden where flowers, shrubs and trees are artistically arranged and managed to provide aesthetic enjoyment. In Japan, this definition is too narrow since many gardens, being composed entirely of rocks and gravel, do not have vegetation (Young 16).

The modern Japanese word for “garden” is teien (庭園), composed of the two characters niwa (庭) and sono (園). In prehistoric times, the term niwa referred to places where ceremonies dedicated to the Shinto kami spirits were carried out. These ceremonial places are thought to have been the areas around sacred objects like trees, rocks, or waterfalls in which the kami were believed to reside (Juniper 69). After the agricultural advances of the Yayoi Period, the term niwa began to refer to the small area of packed clay in front of a house where ceremonial activities like daily chores and greeting guests occurred. At the same time, the word sono developed to describe rice paddies that were flooded for planting. These agricultural practices required extensive modifications to the surrounding land: trees were cleared, fields were leveled, terraces and retaining walls were constructed. “The importance of water is also seen in the sacred ponds and purification rites of early Shinto” (Young 16). Both of these early root words were retained in the formation of the term teien and are a large part of the conceptualization of the Japanese garden.

It was not until the Kamakura period (1185-1333) that Zen ideology started to make an impression on the art of garden design. “A basic principle of Japanese gardening is miniaturization, in which elements such as rocks and ponds are used to represent large-scale landscapes” (Young 25). Large rocks were used frequently, arranged into compositions to represent mountains with their slopes and crevasses. Various trees and shrubs might be pruned and trained into different shapes to represent meadows and valleys or used to provide transitions between the different “scenes” in a garden. Soil might be piled up to create artificial hills and water channeled into streams, ponds, or waterfalls.

This kind of miniaturized garden design is pervasive throughout Japan, but there is, perhaps, no better representation of this confluence of the Japanese teien and the Zen Buddhist philosophy than in the oldest known example of this style of rock garden: the temple of Ryōan-ji in northwest Kyoto.

Ryōan-ji, literally translated as “The Temple of the Peaceful Dragon,” is a Zen Buddhist temple, the grounds of which comprise several examples of Japanese garden design: its famous karesansui (or “dry landscape”) rock garden, as well as a water garden, the Kyoyo Pond with its shrine and cherry trees, and a teahouse and tea garden.

The rock garden at Ryōan-ji is universally hailed as one of the finest surviving examples of the dry, Zen gardens of the Muromachi Period. However, the designer of Ryōan-ji and the date of its construction are a matter of some contention. The site was originally an estate of the Fujiwara clan in the 11th century, when the first buildings and a large pond which is still in existence on the site were built by Fujiwara Saneyoshi. In the 15th century, a powerful warlord by the name of Hosokawa Katsumoto acquired this estate and built his residence on the property. In accordance with his wishes, the estate was converted to a Zen temple and renamed Ryōan-ji sometime around 1450, then placed under the patronage of nearby Myoshinji, a Zen monastery of the Rinzai sect.

This much is known. The point of contention occurs after, with some sources dating the rock garden in Ryōan-ji to the 15th century, commissioned by Hosokawa Katsumoto himself. “The original garden apparently had a covered corridor running through it in a north-south direction, with a view of the garden on both left and right, and a gate at the south end” (Young 167). However, the temple complex of Ryōan-ji was burnt to the ground along with most of Kyoto during the incredibly destructive 10-year conflict of the Onin War.

Once the fighting had settled down, Katsumoto’s son, Masamoto, had the temple rebuilt, and it is unclear the state of the garden during this time. While Young claims that it is most likely that the walled rock garden was created by Masamoto between 1619 and 1680, others claim the temple was built by the legendary monk and painter, Soami. Yet some others claim it was built much later during the Edo period. Two signatures carved into the back of one of the stones in the garden suggest that it may have been constructed by semi-amateur gardeners, possibly of the lower classes.

Even if the Hosokawa family had built a rock garden here in their lifetimes, this still would not settle the debate, as a fire destroyed Ryōan-ji a second time in 1797. After this razing, the garden is believed to have been filled in with debris and a new rock garden constructed on top; this is apparent due to the fact that the grounds inside the wall are raised above the surrounding area. The earliest written description of the garden dates from around 1680 (during the life of Masamoto), which described it as a composition of nine big stones laid out to represent Tiger Cubs Crossing the Water. As the garden presently contains fifteen stones, it is clear that the site has undergone some sort of evolution over the years, only adding to its mystique.

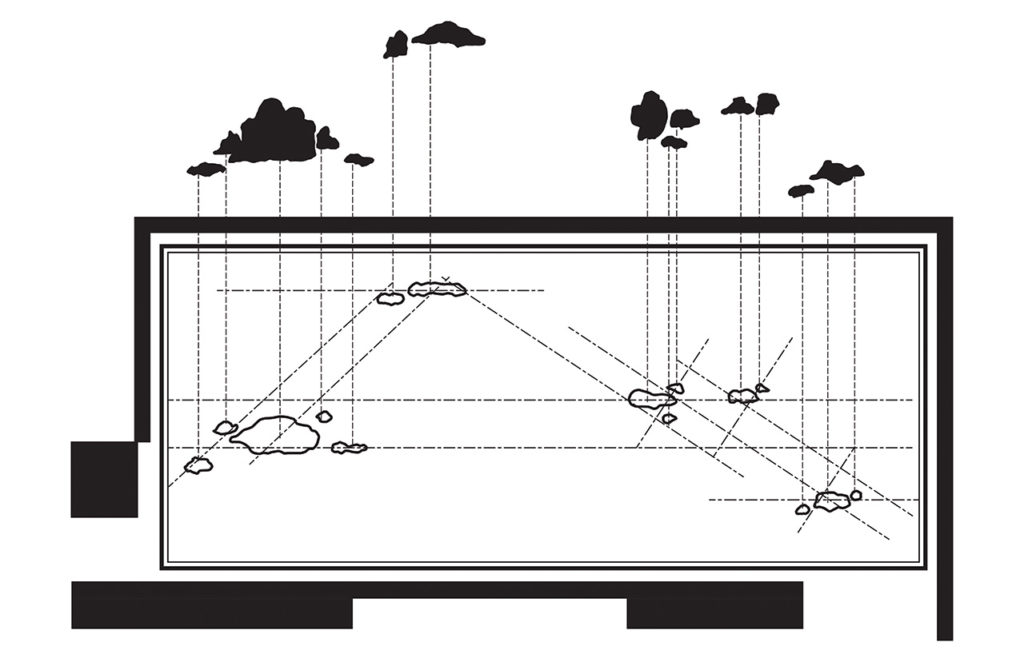

The Ryōan-ji rock garden, as it stands today, is fairly small (about 83 feet by 33 feet) with the longer side stretching from East to West. The fifteen stones are arranged in five groupings surrounded by delicately raked white sand. The garden design is the paragon of the karesansui style, pure in its total lack of water or plants (save only the moss at the base of each rock grouping). The garden is walled on three sides with the South and West sides constructed of a unique material manufactured out of a clay which has been boiled in oil. Over the centuries, this oil has seeped out of the clay, creating an odd patina of subdued lines and colors, exemplifying the aesthetic qualities of wabi sabi. Wabi sabi is a Japanese term, loosely translated as “the beauty of impermanence and imperfection.” The rock garden itself reflects the idea of wabi, or “the solitude and simplicity of nature,” while the patinaed clay wall that serves as the garden’s backdrop reflects the idea of sabi, or “the beauty and serenity that comes with age” (Juniper 2).

The garden is designed to be observed from the north side, where it is lined by the deck of the temple building. It is from this vantage point that visitors are invited to sit and contemplate the elegant simplicity of the rock arrangements.

In the design of Japanese gardens, “the most important elements are structural features” (Young 24). Similar to the French baroque designers like Andre Le Notre, Japanese garden designers used the technique of altered perspective. By making rocks and trees in the foreground larger than those in the background, the result is an illusion of increased distance, consistent with the garden’s representation of larger, natural landscapes.

Another common technique, miegakure (or “hide-and-reveal”), arranges gardens in such a way that not every element in the garden can be seen at once. Often entrances, vegetation, or fences and other structural elements are employed to block the viewer’s perspective. The arrangement of Ryōan-ji’s stones is such that from any vantage point at least one of the stones is hidden from view, making it impossible to see the garden in its entirety.

Another basic principle of Japanese gardens is asymmetry. In an asymmetric composition, no single element achieves dominance. If a garden contains a focal point, it is usually off-center. Rocks and trees are usually arranged into triangular compositions in order to create a balance between the horizontal, vertical, and diagonal forces. We see these principles exemplified rather dramatically in Ryōan-ji, and there is no central element that captures the viewer’s attention.

While there is one rock which is larger than all the rest, it is so far off-center that a balance is created between it and the remaining stones—as if the entire plane were set upon a single fulcrum far from the center of the garden. Add to this the fact that the garden can only be seen from the north side, and an experience is created where the eye moves endlessly among the stones, searching for but never settling on any focal point. There is, thus, “a balance between structural stability and a type of dynamism in which the eye is enticed to trace an interesting route as it moves from one element to another, thereby drawing the viewer into the creative process” (Young 25).

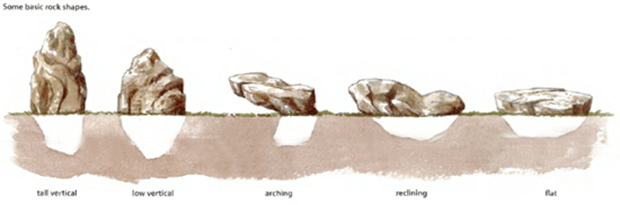

The selection and composition of rocks in this type of Japanese karesansui garden is also of utmost importance. The Japanese language has over a hundred words that describe the different rocks that might be incorporated into a design. Rocks are selected because of their unusual shapes, sizes, colors, or textures—because their sharp, angular planes resemble the rugged mountain peaks of larger landscapes or shorelines. At times (as is the case with Ryōan-ji) they are combined with moss or lichens. Traditionally, these rocks were classified according to their shape: tall vertical, low vertical, arching, reclining, and flat. Depending on the type of rock, it may serve a range of specific purposes within the garden: Round sedimentary rocks worn smooth by rivers are used around the edges of gardens or ponds, rough igneous or volcanic rocks are used as stepping stones or to emulate mountainous peaks, and hard metamorphic rocks are normally used around waterfalls and streams.

Just as the traditional Shinto ceremonial spaces revolved around a belief that kami inhabited these objects, it was also believed that the kami inhabited these spaces only intermittently. As such, the concept of time was incorporated into these gardens via the void space between the elements where kami reside. The concept of ma refers to an interval in time or space that is pregnant with meaning (Young 88). In Japanese architecture, this refers to the empty space waiting for an event to happen, and we can even see this concept reflected in the traditional use of tatami floor mats that fill Japanese dwellings). In Zen Buddhism, the idea of mu refers to this void, a realm of pure potential beyond space and time from which the world of the senses is born. Such ideas are essential to understanding the rocky, graveled courtyards of Japanese gardens–not just empty spaces but sacred areas of worship that exist beyond time and space.

The Zen maxim that the universe can be found within a grain of sand could not be more apt. Sand and gravel are frequently used as representations of this type of void space, raked into patterns, suggestive of flowing elements such as clouds and streams. “By implying movement, sand patterns rely upon the power of suggestion to entice observers to participate in the creative process and to enter into the very fabric of the garden itself” (Young 32). The fluid dynamism of the sand also provides a kind of complimentary juxtaposition to the permanence of the larger rocks, the yin and yang between the eternal principles and the fluid impermanence of nature. It is the transient infinitude that both surrounds us and becomes us from within.

It was during the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) that the ishitateso, the “monks who place stones,” were charged with the task of designing these sacred temple spaces as expressions of their devotion to the Zen Buddhist ideologies. Using only rocks and sand, these monks sought to create microcosmic versions of the larger cosmic order, beckoning viewers to forget themselves and become immersed in the seas of gravel and mountains of stone. “By loosening the rigid sense of perception, the actual scales of the garden became irrelevant and the viewers were able to then perceive the huge landscapes deep within themselves” (Juniper 71). Just as our eyes only perceive dry ruts hashed into the sand, so our minds are unaware of the torrential river of the infinite cosmos.

Unlike the grand landscapes of European designers, which are designed to be overwhelmingly large and impressive, the karesansui garden is intimate and subtle, meant not to be awe-inspiring and viscerally appealing but to invite the viewer to sit in contemplation of the garden as a metaphor for the universe beyond and within.

At the southern entrance to the temple of Ryōan-ji, there sits a famous stone water basin [cover], known as a tsukubai, the purpose of which is for visitors to ritually purify themselves by washing their hands before entering the temple. On the rim of this basin are four Japanese characters that read, “I learn only to be content,” a Zen saying which implies that the secret to happiness rests in finding contentment with one’s circumstances, rather than suffering hopelessly in search of that which may never come to be.

In the centuries that have passed since Ryōan-ji was first constructed, our world has become a much faster place. We seem to be compelled to find ways of filling every moment with some kind of activity or distraction, even fearing the void between moments which the Zen Buddhists believe to be so full of potential. Instead of spending time to reflect on the sublime cosmos that surrounds and becomes us, we search desperately for ways to distract ourselves from it, allowing our senses to become increasingly overloaded and dulled to the perception of subtle potentiality. I believe that, as we find ourselves immersed in this chaos, we must teach ourselves once again to be receptive to the silence that connects all this noise, so that we might not lose ourselves in its volume.

Works Cited

- Young, David and Michiko. The Art of the Japanese Garden. Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2005.

- Juniper, Andrew. Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence. Tuttle Publishing, Tokyo, 2003.

- Van Tonder, Gert, et al. “Perception Psychology: Visual Structure of a Japanese Zen Garden.” Nature, 2002.

- Seo, Yoonjung. “Ryōanji (Peaceful Dragon Temple).” Khan Academy, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ap-art-history/south-east-se-asia/japan-art/a/ryoanji

- Jackson, Richard. “Kyoto 4 – Ryoan-Ji Temple and Garden.” The Garden Visitor, 1 Dec. 2017, http://thegardenvisitor.co.uk/kyoto-4-ryoan-ji-temple-garden/.

- “Curious Affinities I.” Figure ground game, https://figuregroundgame.wordpress.com/tag/ryoan-ji/

- “Ryoanji Temple.” GaijinPot Travel, 25 Oct. 2018, https://www.travel.gaijinpot.com/ryoan-ji-temple/.

- “Otsu-In Temple.” Kyoto Moon, 18 Mar. 2018, http://kyotomoyou.jp/myoshinji-daishinin-20160421.