Introduction

~ 10 minutes

From ancient cave paintings to post-modernism, one of the fundamental traits of humanity is our ability to create. Anthropologist Franz Boas once wrote that “there are no peoples without religion or without art” (Boas 634), showing that design exists as a formational factor in all the world’s cultures.

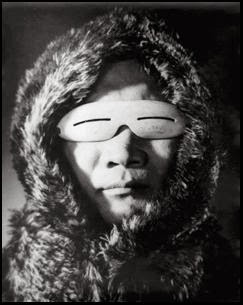

Throughout human history, we see examples of art and design as products of our ingenuity (like these clever Inuit sunglasses that protect against snow blindness). As the environmental factors people face vary from region to region, so do the designs they create. These designs, in turn, change the way people interact with the world, affecting the values and traditions emerging out of different cultures. This is the natural interplay between design and culture, with design arising as a product of cultural experience.

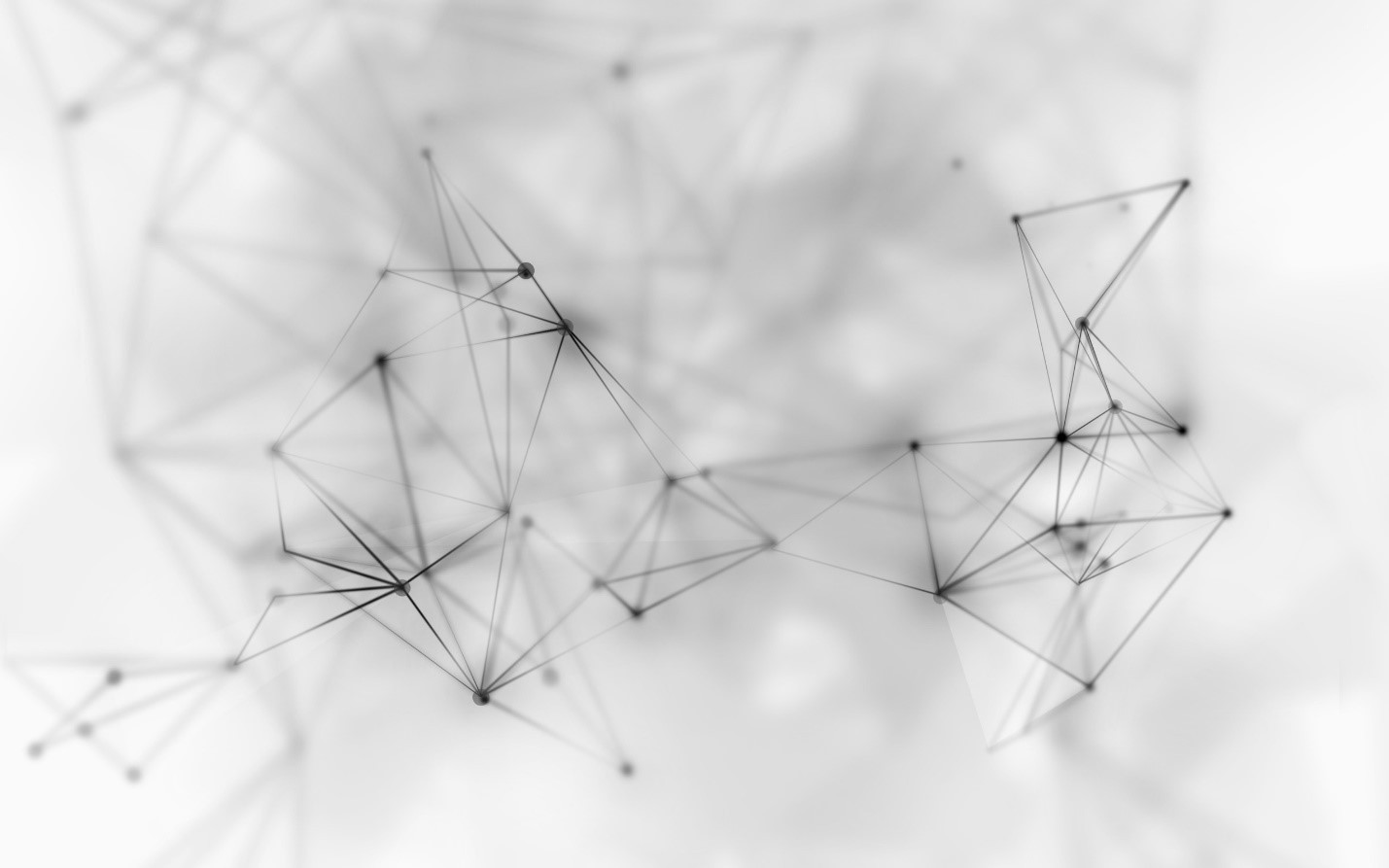

However, the vast majority of issues we face today are human-made, and these problems are ever-shifting. Centuries of colonialism and globalization have made our cultural systems into a twisted jumble of conflicting meanings. As a result, the problems that arise within these systems are based in a web of tangled connections that is perpetually unstable. These problems are what designer Horst Rittel famously dubbed “wicked problems:”

a class of social system problems which are ill-formulated, where the information is confusing, where there are many clients and decision makers with conflicting values, and where the ramifications in the whole system are thoroughly confusing.

(Churchman)

If you add to this the very real limitations on time and resources facing most design projects, you have a situation where, unfortunately, these wicked problems have no perfect solutions—only better or worse ones. A project whose aim is to bring healthy food options to rural and low-income neighborhoods might require ten years of research and development but only have the resources for six months. And so, the products of design often compromise what is necessary, what is possible, and what is plausible.

Designing for this unstable world is like trying to rearrange a spider’s web without breaking it. The practice of design must be exceptionally dynamic if it hopes to perform surgery in these twisted strands. To even begin to approach these problems in a lasting way, “we need to pursue design practices which weave themselves through the social fabric without damaging it” (Douglas). But this is still not enough; to cause real, systemic change, design must not only be able to weave itself through the social fabric but must also be able to grow organically within that fabric as part of the same entity. To extend the metaphor: only a spider can change its web.

As design theorist Christopher Crouch writes, “collaborative design principles, where problems are addressed by designer and user together, are often the way forward in dealing with complex design problems” (Crouch 16). To grow design from within tangled cultural systems, we must re-position designers not as the authors of change, but as facilitators which enhance stakeholders’ abilities to bring about change for themselves.

Complex systems are shaped by all the people who use them, and in this new era of collaborative innovation, designers are having to evolve from being the individual authors of objects… to being the facilitators of change among large groups of people.

(John Thackara 7)

Put simply, the role of the designer must shift from someone who designs for users to someone who designs with stakeholders. This, of course, implies a release of control which could make some designers at least a little uncomfortable. However, the benefits of this are potentially manyfold: Not only would the products of this collaboration be more culturally sustainable, but enabling stakeholders to engage in formal design practices themselves would re-position designers as the influencers of cultural experience—a much loftier goal that would allow the work of design to continue beyond the scope of project deadlines.

To borrow from Sir Walter Scott: Oh, what tangled webs we find when first we practice to design. The strange and tangled social webs we have woven for ourselves grow more chaotic by the moment, but it is within these frayed filaments of cultural systems that we may find the true potential of the designer—not as a mere meddler in other people’s problems but as an enabler of better, more egalitarian, futures for all humanity.

Methodology

Combining methods from cultural anthropology, design thinking, participatory design, user experience design, and cultural dimensions theory, The Social Design Toolkit proposes a hybridized workflow called participatory design thinking, which may enable designers to better identify the biases that impact design outcomes. This workflow embeds crowd-sourced, participatory activities directly into the established design thinking workflow, helping designers instigate change from within communities by ceding some decision-making power to community members and building upon local knowledge.

If we consider design to be the act of planning an object, system, or activity, this suggests that the purpose of design is ultimately to bring about some kind of change; perhaps a change in culture, experience, or behavior. If we compare this with a discipline like cultural anthropology, where the purpose is to study people and the cultural meanings found in societies, then we begin to see where these disciplines might overlap.

…culture and design are not separate analytical domains or extensions of each other. Rather they are deeply entangled, complex, and often messy formations and transformations of meanings, spaces, and interactions between people, objects, and histories.

(Otto 13)

The products of design are embedded in and imbued with cultural meaning. The emergent field of design anthropology holds that—in order for design to be culturally relevant—the methods used by designers must be similarly aligned with understandings of the cultural traditions, precedents, and belief systems of the people for whom design is intended. By adopting an anthropological mindset, designers can attempt to shift their focus toward broader social contexts, emphasizing the experiential aspects of design.

Several design methodologies have attempted to accomplish this. design thinking in part aims to bridge the gap between designers and stakeholders by positioning empathy at the head of its process. Design thinking is an incredibly useful methodology for ideation and prototyping, but when not supplemented by deeper, qualitative, participatory research, it is still a designer-centric way of thinking. In order to connect design to real-world experience at a deeper level, we must go beyond mere empathy and find ways of bringing stakeholders into the process.

In user experience design, we see something much more dynamic happening, where designers are including stakeholders in the design process by conducting user research with them directly through a range of observational and participatory methods. What this provides is a much more authentic connection to stakeholders that helps bridge this gap between designers and users. UX research is currently most utilized in the design of technologies and digital interfaces, but with the right tact this methodology can easily be expanded to different types and scales of human-centered design.

According to Antoinette Caroll’s Equity-Centered Community Design:

A designer is anyone who has agency to make a decision, however small, that will impact a group of people or the environment… In fact, a person may not have formal training or an official title as a “designer” to be a designer.

(Carroll 4)

This is a relatively new mindset for the design industry, but if we think back to designs like those Inuit sunglasses, we see that it is an incredibly old concept for humanity. This mindset emphasizes local knowledge as being equal to design knowledge, which repositions designers not as the sole creators of cultural innovation but as instigators of change within communities who build upon local knowledge by embracing people’s natural ability to solve problems.

Participatory design thinking aims to combine these methodologies through an understanding of their strengths and shortcomings—allowing them to supplement one another. The Social Design Toolkit provides the tools for designers to connect to, collaborate with, and empower stakeholders as a necessary part of creating experiential solutions. For example, this might mean that instead of designing temporary shelters for the homeless, designers would work with the homeless to better understand the systems that led to their circumstances and to find ways for them to reintegrate with society.

Social design is a process of collaborative, root-cause analysis that initiates change from within cultural systems in experiential ways, rather than by simply implanting commercial products into those systems.