Participatory Design Thinking

~ 8 minutes

The products of design have the capacity to alter the ways people interact with and interpret reality, and the majority of designers are influenced by cultural experiences that differ from those of stakeholders. For instance, if designers educated at metropolitan universities were to design for farmers in rural areas or even at-risk youth within a 10 minute drive of campus, they would lack fundamental understandings about these people’s lives. The implications of this are nothing short of profound, and Design cannot ethically operate within this margin of error.

Instead, we must make attempts to reconnect design to its appropriate cultural anchors. We do this not by simulating or speculating about cultural experience, but by embedding that experience into the design process. What that usually means is not just making assumptions about what people want or need but interacting with them on a personal level that allows them to show you what they need.

Participatory Design

Participatory Design (sometimes called “co-design”) was originally borne out of Scandinavian trade unions in the 1970s, as an attemp to bring stakeholders into the design process. According to the Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design:

Participatory Design can be defined as a process of investigating, understanding, reflecting upon, establishing, developing, and supporting mutual learning between multiple participants in collective ‘reflection-in-action’. The participants typically undertake the two principal roles of users and designers where the designers strive to learn the realities of the users’ situation while the users strive to articulate their desired aims and learn appropriate technological means to obtain them.

Participatory Design has always given primacy to human action and people’s rights to participate in the shaping of the worlds in which they act.

users are… asked to step up, take the pen in hand, stand in front of the large whiteboard together with fellow colleagues and designers, and participate in drawing and sketching how the work process unfolds as seen from their perspectives.

(Simonsen 2, 4, 5)

This is a process of creating reciprocal working relationships that empower stakeholders, designing in such a way that enables people to have a stake in their own solutions. Rather than designing for passive users, it is a process of elevating all stakeholders to active participants in the design process.

Participatory design does not operate within the industrial paradigm of designers telling users how they are going to solve their problems but in a more dynamic paradigm whereby designers guide stakeholders through critical thinking exercises that elucidate locally sustainable solutions. Through this, we can break free of the mindset that design is a commercial activity and, instead, focus on creating experiential solutions that work on a cultural level. Through participatory design, designers become not the direct agents of change but, rather, the conduits through which people can improve their own lives.

Design Thinking

The most prominent design methodology in use today, Design Thinking, is itself an iterative process that revolves around designers empathizing with stakeholders and then brainstorming and prototyping possible solutions. It is a highly valuable workflow for encouraging designers to collaborate with each other, but—in practice—it lives mostly on Post-It notes in the studio, where designers gather around a whiteboard to speculate about the needs of stakeholders. What is missing from this equation is the opportunity for stakeholders to create their own solutions.

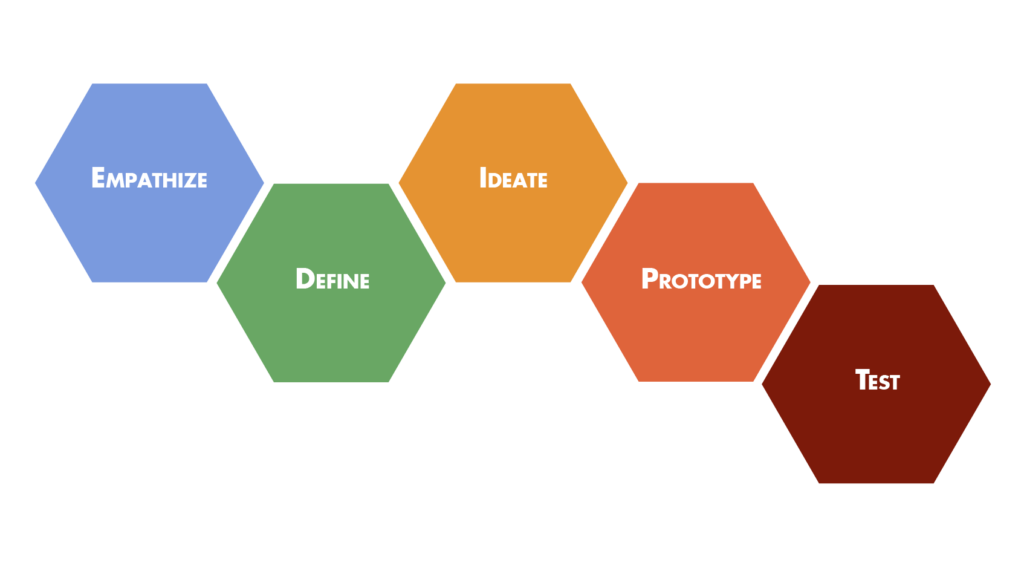

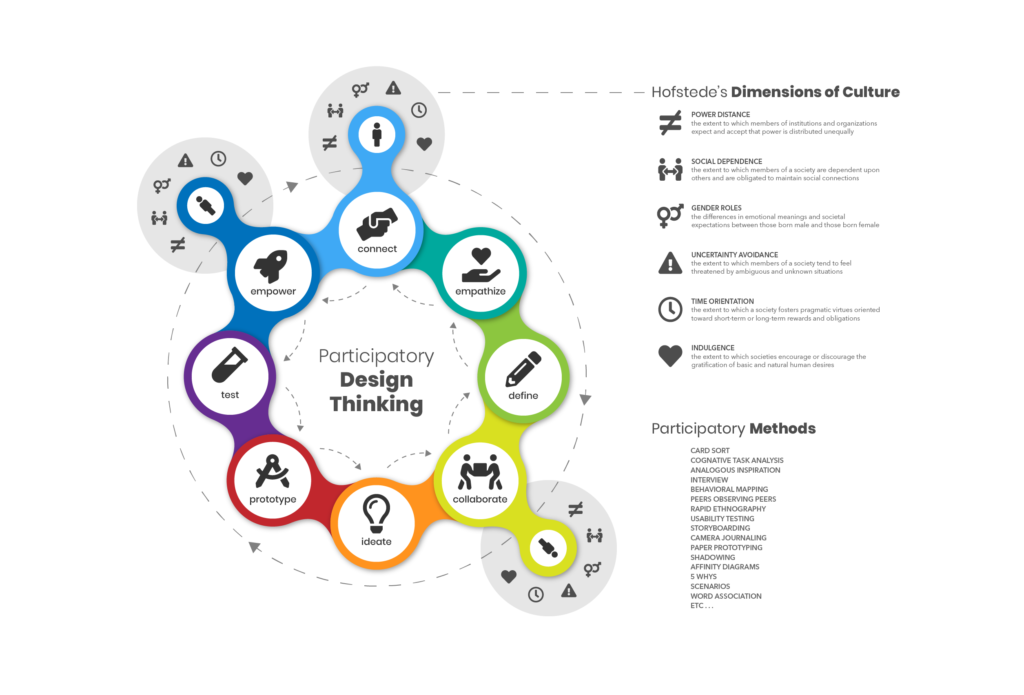

If we examine a typical chart of the Design Thinking process (like the one pictured below from the Stanford D. School), we may find that there are several fundamental steps that seem to be completely missing: steps which enforce the need to “Connect,” “Collaborate,” and “Empower.”

By omitting the needs to collaborate with and empower stakeholders, Design Thinking limits its scope and shows a general disregard for local methods. What this dynamic tends to generate is design solutions which fit the designer’s process rather than stakeholders’ needs. “This is a top-down, outside-in approach. It doesn’t work well now because complex systems, especially human-centered ones, won’t sit still while we redesign them” (Thackara 213). Design is “of a moment” and “will always be context-specific—responding to the needs and wants of a population, situation, or geography that is current and contemporary” (Allen 2). Because the cultures for which we design are constantly evolving, the design process must evolve as well.

The flaw in many designers’ approaches to Design Thinking, I believe, is found in the misrepresentation of “empathy.” We hear a lot these days about the need for designers to empathize with stakeholders, but empathy is a kind of ambiguous term, which many designers interpret superficially, leading to the belief that speculations about stakeholder needs can garner sufficient insight into people’s lives (as if wearing a blindfold for a day will encapsulate the experience of being blind).

Despite its efforts to generate empathy, Design Thinking is still a “designer-centric way of thinking.” There is no substitute for actual experience, and Design Thinking has become a top-down approach based on simulating this experience. When not supplemented by deeper qualitative research, these simulators actually further exclude stakeholders from involvement in the design process by replacing them with props and gadgets.

Participatory Design Thinking

As design theorist Richard Buchanan notes, “what many people call ‘impossible’ may actually only be a limitation of imagination that can be overcome by better design thinking” (Buchanan 19). By expanding Design Thinking to include participatory methods, we would alter the purpose of design itself away from that of an object-driven practice and toward that of an experiential activity undertaken by the designer and stakeholders as mutual collaborators (Allen 3). By emphasizing stakeholder engagement and collaborative design, the role of the designer can begin to shift from that of an exogenous creator to that of an enabler of cultural growth.

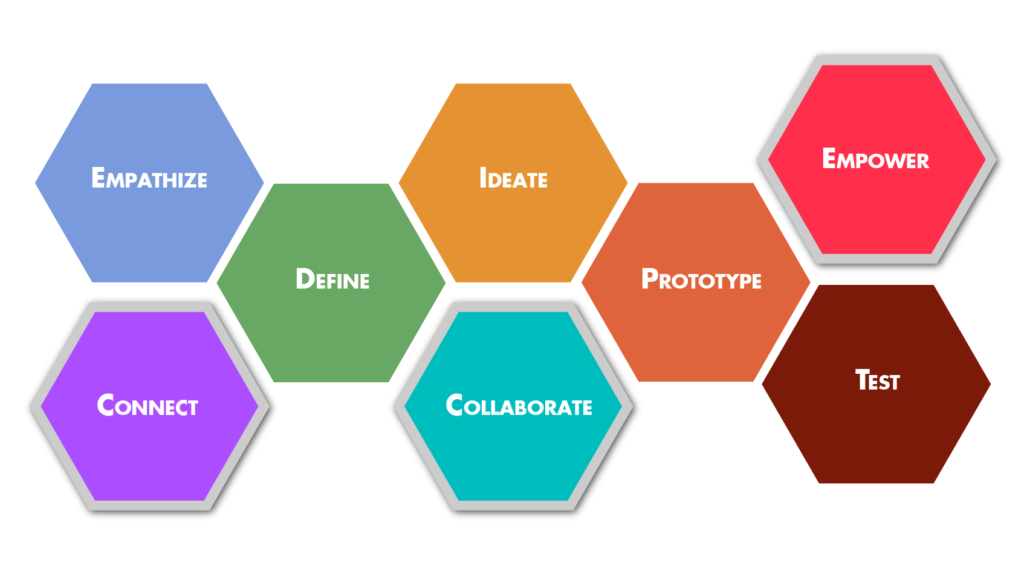

To accomplish this, I propose a new model of Participatory Design Thinking that contains certain junction points embedded in the workflow that allow these methodologies to overlap. This is a more internally disruptive model, placing human experience at the core of every design decision and allowing designers opportunities to question the assumptions that cloud understanding. These junction points would push designers to connect and collaborate with stakeholders through participatory activities.

The purpose of overtly embedding participatory methods into the Design Thinking process would be to force designers to challenge their preconceptions. This is meant to open the design process to alternative ways of thinking and doing and to instigate change from within communities by ceding some decision-making power to community members. By expanding Design Thinking to a more open and inclusive process, we enhance the reciprocal relationship between designer and stakeholder, encouraging the integration of design skill with cultural knowledge.

See how to use Participatory Design Thinking as part of the Social Design Workflow.